Why the Balkans?

Unveiling the challenges of hydropower in the Balkans

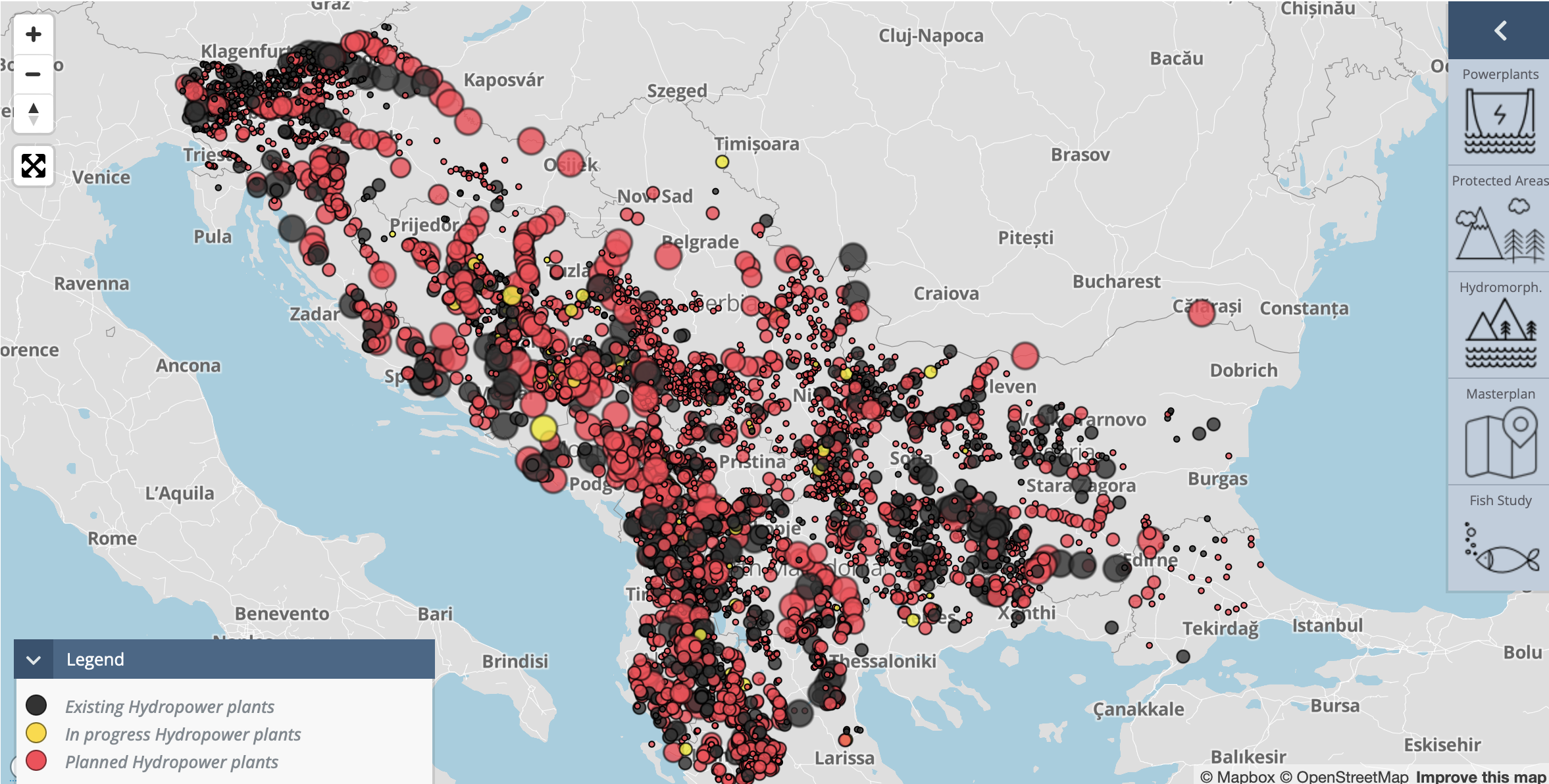

The rivers in southeast Europe are the most valuable and intact rivers in Europe. They also harbour Europe’s highest concentration of endemic fish species. From the amazing sinking rivers of the Dinaric karst, to some of the world’s deepest and wildest canyons, to the last remaining European free-flowing large rivers, they are the hotspot for the continent’s freshwater biodiversity. So why does the Balkans, with its breathtaking landscapes, witness a surge in hydropower projects? Home to 100-200,000 km of freshwater rivers and streams, it now stands at a critical crossroads. With 1,726 hydropower plants already operational, 108 in progress, and a whopping 3,281 in the pipeline, the region is witnessing a surge in dam development that raises serious questions about its economic motives, environmental impact, and policy challenges.Traditionally entwined with coal, hydropower has long been a mainstay in the power systems of Southeast Europe. This trend persists, especially in countries like Albania, Montenegro, and Croatia, where hydropower claims a significant share.

Over the last two decades, the region has witnessed a proliferation of 'small' hydropower plants, each under 10 megawatts, often nestled in protected or ecologically sensitive areas. However, the journey to build larger, greenfield hydropower plants, surpassing the 10 MW mark, has been fraught with challenges. Only Albania and Slovenia have succeeded in such endeavors.

Despite this, ambitious plans for new large hydropower projects persist, siphoning resources away from potentially faster and more economically viable alternatives. Bosnia and Herzegovina, in particular, maintains its ambitious stance, although it hasn't completed a single greenfield large hydropower plant in the last decade.

This brief unveils the risks associated with hydropower projects in Southeast Europe, painting a challenging future due to climate vulnerability, unique biodiversity, legal complexities, public resistance, and financing issues. It contends that the region's pursuit of hydropower will become increasingly difficult. Moreover, it suggests investments with lower risks that can guide the region towards a more sustainable energy system.

The reliance on hydropower in the Western Balkans is evident, constituting around one-third of electricity generation from 2010 to 2020. Albania, for instance, is almost entirely hydropower-dependent for domestic generation, while Montenegro relies on it for around 50 percent of its electricity. Bosnia and Herzegovina leans on hydropower for about a third of its electricity generation.

As renewable energy gained political traction in the late 1990s and early 2000s at the EU level, Southeast European nations perceived it as an opportunity to expand hydropower. Familiarity with this energy source, coupled with estimates of massive untapped potential, fueled their enthusiasm. However, these claims often rely on outdated estimates, revealing a time when rainfall was more predictable, opposition was scarce, and knowledge about the region's biodiversity was limited.

The past 15 to 20 years witnessed the construction of hundreds of 'small' hydropower plants, each under 10 MW. These projects, often spurred by feed-in tariff schemes, wreaked havoc on rivers and streams, especially in protected areas. However, as these schemes are phased out, interest in such projects is waning.

In contrast, endeavors to build larger greenfield hydropower plants (above 10 MW) have been met with limited success, with only Albania and Slovenia achieving this feat. Albania has added over 600 MW of large hydropower since 2010, while Slovenia has successfully built several plants. Other Southeast European nations have mostly contributed smaller plants that contribute minimally to the overall electricity supply.

Despite these challenges and a low success rate, plans for new large hydropower projects persist, particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This not only diverts resources but also impedes the development of quicker and more economic alternatives.

The region faces a critical juncture — either continue down a path laden with environmental, social, and economic risks or explore alternative, more sustainable energy solutions. The annex provides profiles of nine particularly high-risk projects, urging a reconsideration of the region's energy trajectory.

The question remains: Will the Balkans forge ahead with hydropower, facing intensifying challenges, or embrace alternatives for a more balanced and sustainable energy future?

Resource: Why hydropower in southeast Europe is a risky investment

Historical Significance:

Hydropower, entwined with coal, has long been a cornerstone of Southeast Europe's power systems, prominently featuring in the Western Balkan countries. This dynamic duo, alongside other sources, fueled approximately one-third of electricity in the Western Balkans from 2010 to 2020. Albania stands out, almost entirely dependent on hydropower, while Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina rely on it for approximately 50 percent and one-third of their electricity generation, respectively. Other regional players like North Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia also exhibit varying degrees of dependence on hydropower.

Political Shifts and Renewable Energy:

As the EU championed the development of renewable energy in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Southeast European governments saw it as an opportunity to expand hydropower. Familiarity with this energy source, coupled with estimates of untapped potential, fueled their enthusiasm. Governments often claim regions with high untapped hydropower potential, relying on outdated estimates from a time when factors like rainfall were more predictable, opposition was limited, and the region's biodiversity was less understood.

Small-Scale Hydropower Onslaught:

The past 15 to 20 years witnessed the proliferation of 'small' hydropower plants, each under 10 MW, wreaking environmental havoc on rivers and streams. Fueled by feed-in tariff schemes, these projects often encroached upon protected areas and highly sensitive habitats. As these tariff schemes are phased out in most countries, interest in such projects has dwindled. Challenges in Large-Scale Hydropower Endeavors: Attempts to construct greenfield hydropower plants exceeding 10 MW faced significant hurdles, with only Albania and Slovenia successfully navigating these challenges. Albania, for instance, has added over 600 MW of large hydropower, while Slovenia has accomplished the construction of several plants. In contrast, other countries in Southeast Europe primarily contributed smaller plants that made minimal contributions to the overall electricity supply. Bosnia and Herzegovina, although ambitious, failed to complete a single greenfield large hydropower plant in the last decade.

A Looming Surge:

Despite a low success rate, the region faces a surge of over 3,500 planned hydropower plants, driven by economic motives and outdated policies. The allure of "Clean, Green Hydropower Dams" is debunked. The question emerges: Are the perceived gains from these projects, which pose a significant toll on the environment, justified? Particularly when viable alternatives like solar and wind exist.

Global Perspective on Alternatives:

Globally, renewable wind and solar energy outshine small-scale hydropower in job creation, with four to five times the employment opportunities. Notably, 91% of hydropower projects in the Balkans, including many diversion dams, produce minimal energy and have substantial adverse impacts. In contrast, wind and solar projects offer quicker construction timelines and average cost overruns of less than 10%, making them more efficient and less prone to corruption. As the Balkans stand at this critical juncture, grappling with the impending surge of hydropower projects, the need to reconsider energy strategies becomes paramount. The path chosen will determine the fate of the region's rivers, biodiversity, and the overall well-being of its communities.